This is the story of two lighthouses.

One is near a neighborhood, the other is gone forever.

Introduction

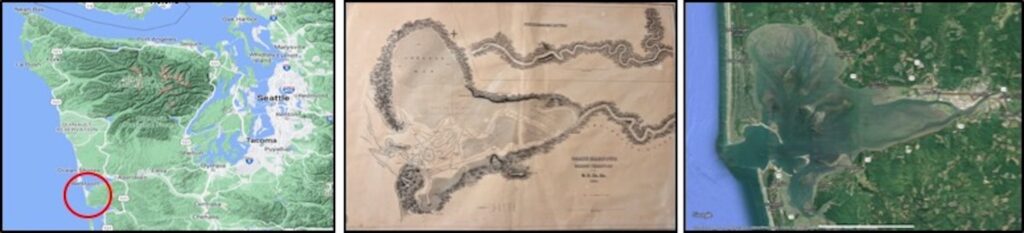

A recent trip to a small town in southwest Washington gave me the idea for this story. At one end of a coastal road, a lighthouse built 120 years ago near the edge of the water was now thousands of feet from shore and surrounded by a forest. Sixteen miles to the south, another lighthouse built 40 years earlier was lost to the sea, along with a small community.

As it turned out, the first part of the story was false, and the second was far worse than I could have imagined. Along the way, I learned a lot about what it means to live next to an ocean, and quite a bit about big rocks, little rocks, and butterflies.

Aqua and Terra Incognita: The Unbuilt Environment

On May 7, 1792, Captain Robert Gray on his ship, the Columbia Rediviva, became one of the first non-native people to enter what is now known as Grays Harbor. The area was far from devoid of human habitation: native Americans had been living along this coast for thousands of years, and Gray wasn’t even the first visitor to show up. Sir Francis Drake, Vitus Bering, James Cook, and George Vancouver had all been in the region earlier. There is even a story about Hwui Shan, a Chinese adventurer, visiting in 458 AD.

Pioneers from states like Missouri, Ohio, and Illinois began showing up in the early 1850s and soon set to work reshaping the environment. Over the next 60 years, the newcomers built three rather large structures near or in the ocean that would provide them with their first of many lessons in unintended consequences:

- In 1858, a lighthouse was built on Cape Shoalwater, a large headland at the mouth of what is now called Willapa Bay.

- In 1898, another lighthouse was built on Point Chehalis near the town of Westport.

- In the early 1900s, two rock jetties were constructed on the north and south entrances to Grays Harbor to protect the harbor and enable maritime traffic.

The jetties and lighthouses played a role in a dynamic and complicated story that is still being told 170 years later.

The Lighthouse Next Door

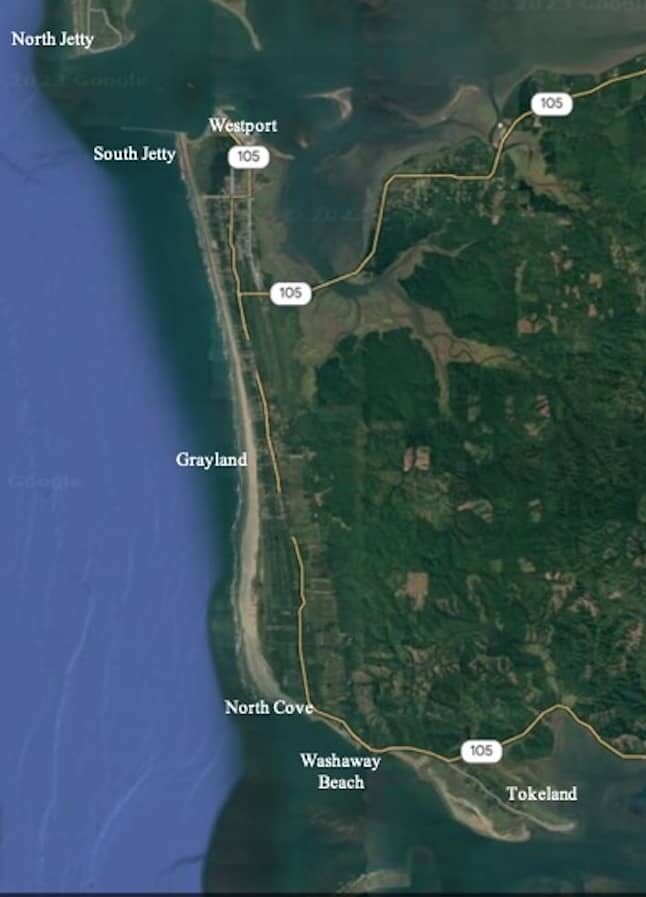

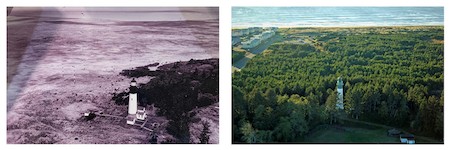

The first thing visitors notice about the Westport Light is that it’s not situated near the water.

Instead, it’s surrounded by trees and located several thousand feet inland near a neighborhood.

Not the first image you might conjure up when you think about lighthouses…

Even so, it is an impressive structure and is the tallest lighthouse in Washington State at 107 feet.

135 steps lead to the top.

Some believe it was moved to its present location; others suspect the presence of the nearby jetties somehow changed ocean circulation and sediment transport patterns, causing a massive amount of sand to pile up (accrete) along the adjacent beach over the years, meaning the lighthouse didn’t move east; the beach moved west. Two plausible explanations exist.

Neither is correct.

A few years ago, the folks at the Westport Maritime Museum found an old drawing by the US Army Corps of Engineers (Army Corps) from 1900 that showed the lighthouse was intentionally sited well away from the water on one of the highest sand dunes in the area. It turned out to be a smart decision, and probably why there still is a Westport Light. This will come up again when we talk about its unlucky sister lighthouse, the Willapa Light.

As you can see above, the area around the lighthouse has changed a lot over the years. In the 1970s, pine trees were planted to help stabilize the sand. They spread out over time to create the dense forest present today. As you will see, despite the vegetation, the area is still susceptible to erosion from the sea.

Imagine for a moment the environment that Robert Gray saw in 1792 — an area only lightly touched by human activity. A century later, a decision is made to build rock jetties on both sides of the harbor to make it safer for vessel traffic.

What could possibly go wrong? Let’s find out.

The Grays Harbor Jetties: Big Rocks in a Bigger Ocean

“As with almost all projects aimed at controlling the ocean, the Westport Jetty’s tale is full of unintended consequences and frustrations.” Westport Jetty – Before & After

The story of the Grays Harbor jetties is complicated. The main theme that emerged from sometimes conflicting historical accounts I read was that since their creation, the north and south jetties have had a complex relationship with the ocean, the surrounding beaches, the local population, and each other. They were difficult to build, are expensive to maintain, and remain highly unpredictable. Over time, they’ve required a host of engineering fixes that would often address one problem while creating another.

The construction techniques reflected the technologies of the times, which mostly involved brute force, steam engines, big rocks, and trial and error. For the South Jetty, the first step was constructing a trestle out into the ocean that could accommodate heavy equipment, then dumping a lot of big rocks into the water on a bed of brushwood sticks to keep them from sinking in the soft sand. The basic process is shown below:

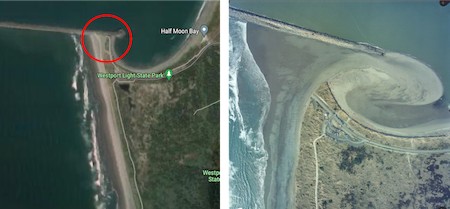

The satellite image below gives perspective of the size of the project. The South (Westport) Jetty was completed in 1902 and was a bit less than 14,000 feet long. Quite a bit of it is underwater now. The North Jetty was constructed between 1907 to 1916, and is actually about 3,000 feet longer than its southern sibling, though much of it was built on the tide flats not shown in the image.

Upon completion, the two jetties began to do their job: protect vessels entering and leaving the harbor and increase the velocity of water leaving at ebb tide to scour away the sand and keep the channel navigable.

Unfortunately, strong ocean currents soon undermined the rocks, and the jetties began to sink. By 1935, the South Jetty was about five feet below low tide, and the North Jetty had sunk about two feet. More big rocks were added between 1935 and 1942, and again in 1966 and 1975 for the South and North Jetties, respectively. Each rebuild seemed to create a new set of challenges (and consequences).

One of the bigger ongoing issues involved how the jetties interacted with nearby shorelines. Depending on the state of jetty repair, an adjacent beach might gain sand (accretion) or be subject to erosion at a frightening rate. Either scenario was problematic. For instance, after the South Jetty was rebuilt in 1940, significant erosion began to threaten Point Chehalis. Based on modeling results available at the time, the Army Corps determined the best way to reduce the problem was to intentionally allow natural deterioration of the outer 6000 feet of the South Jetty. In doing so, a mile of hard work was given back to the sea.

As time went on, the Army Corps launched dozens of projects to “tweak” the system, yet problems continued to emerge. They discovered in the mid-1980s, for example, that the beaches just south of the South Jetty had retreated over 300 feet, eroded by the sea. They studied the problem.

Then in December 1993, the Pacific Ocean found a weak point at the base of the South Jetty near Westport, and this happened:

It took a year to repair the jetty breach, and in the meantime, local residents watched helplessly as large chunks of their beaches were carried away by the ocean and nearby structures were severely damaged, as shown below.

This was both a cautionary tale and a wakeup call: whether they liked it or not, their futures were connected to the health and well-being of the two jetties protecting Grays Harbor.

As bad as it was, the 1993 Westport jetty breach paled in comparison to what had been going on just 16 miles to the south.

The Lost Lighthouse and Washaway Beach

“When you see a home … half on, half off … the beach, it’s like, ‘Wow, there goes somebody’s memories, somebody’s family home.” Jayne Peterson

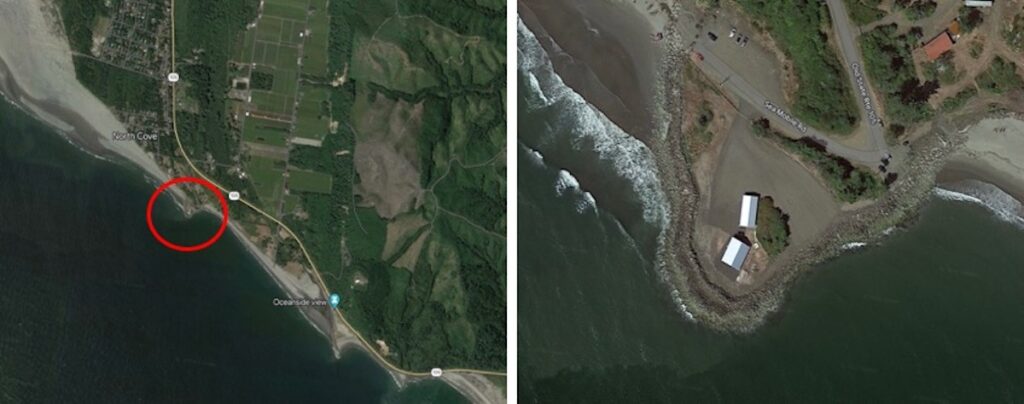

The drive south on Highway 105 from Westport to Tokeland weaves through small communities, state parks, beach access points, and cranberry bogs. Just past the community of North Cove, a small sign points to “Old Highway 105,” a short road that ends abruptly at an odd little peninsula of land containing a private home and shop. It stands like a fortress, protected from the sea by large rocks. Out to the southwest is open water where a community and a lighthouse used to be.

Welcome to North Cove, aka Washaway Beach — an area with one of the highest rates of erosion on the Pacific Coast. Every year on average, the beach moves 100 feet farther inland.

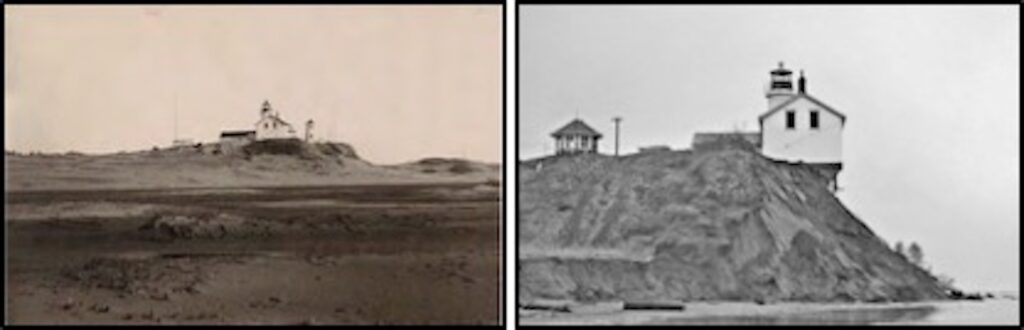

The Willapa Bay Light, one of the first lighthouses built in Washington State (1858), was situated here on what was then called Cape Shoalwater. It would last only 80 years. Abandoned in 1938, the lighthouse was deemed a threat to public safety and demolished in 1940. The cape it was built on disappeared beneath the waves 40 years later.

This turned out to be a bad place to build a lighthouse, or anything else, for that matter.

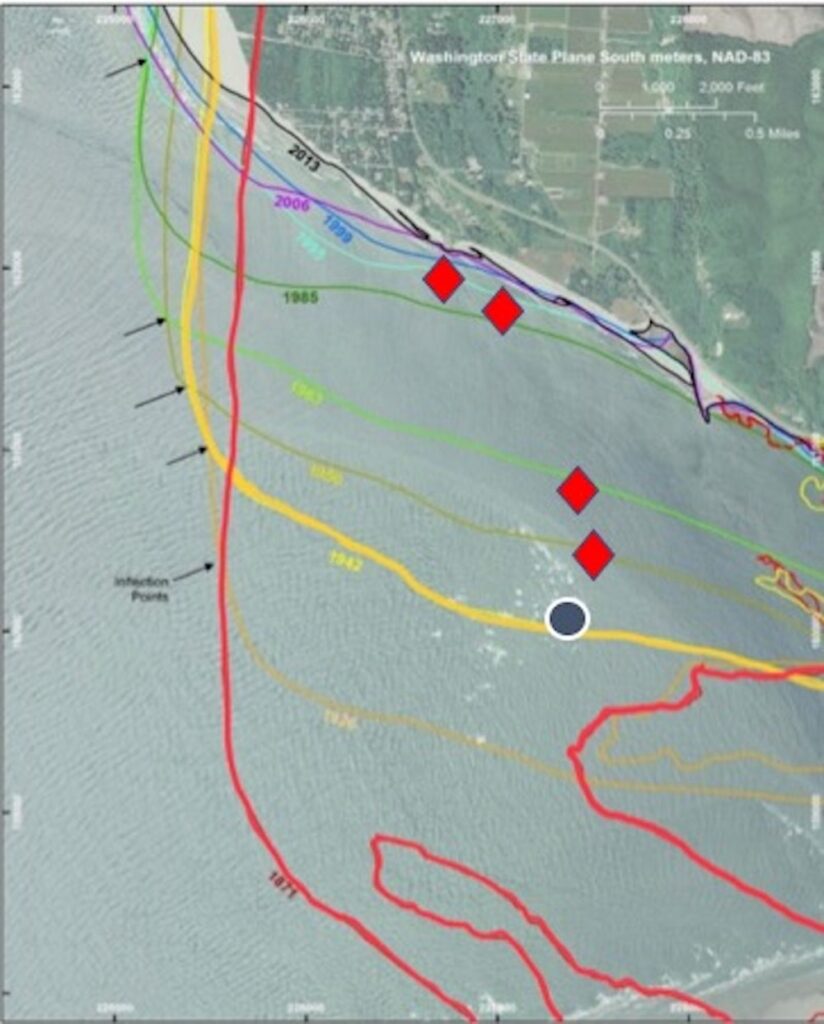

I created the image below from multiple information sources to show how the shoreline has changed over time. The red line is the approximate outline of Cape Shoalwater in 1871, about 20 years after the lighthouse was built. The black dot is the approximate location of the Willapa Light on what was then a lightly vegetated dune environment. By 1942, large portions of the cape had disappeared, along with the lighthouse, as indicated by the yellow line. The diamonds denote locations of a series of navigational towers that were built (and lost to the sea) from 1941 to 1998, with each new tower situated closer to the retreating shore. The thin, black line in the image represents the 2013 shoreline. More has been lost since then.

Historical records reveal a struggle similar to that faced by the builders of the Grays Harbor jetties to the north. Within a decade after the lighthouse was constructed, erosion of the cape and shifting sands made occupying and resupplying problematic. Plank roads were constructed, vegetation was planted, and bulkheads and fences were built to stabilize the area — all to no avail. Sometimes the wind created dunes high enough to completely block the view of the light. Eventually, the lighthouse keepers, Army Corps, and Coast Guard gave up. The lighthouse was lost.

After the sea took the lighthouse, it came for the community of North Cove.

To date, the ocean has washed away approximately five square miles of land (the equivalent of 3,200 acres or 2,400 football fields) in this area. The losses included private homes, small businesses, a Coast Guard station, a schoolhouse, a cemetery, a grange hall, and a national wildlife refuge. All gone.

Almost everyone agrees that the northward migration of the Willapa Harbor entrance channel is part of the problem, and some speculate that the jetties at the mouth of the Columbia River 40 miles to the south (built in the late 1800s) are also involved, along with the hundreds of dams built on the river since the 1930s. Every coastal engineer that has worked at Washaway Beach has come away with a few new ideas about what’s going on and a renewed respect for the power of the sea.

I personally believe butterflies have something to do with it.

Big Rocks, Little Rocks, and Butterflies

Roughly 20 years after the Willapa Light fell into the sea, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology discovered an odd thing about a weather simulation model he was working on: if he made a small change to one of the twelve variables, like rounding a number from 0.506127 to 0.506, and then ran the model a second time, the new result was dramatically different from the first.

Edward Norton Lorenz published his results in 1963 under the ponderous title, “Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow.” Initially ignored, it later became a seminal part of Chaos Theory, and the phenomena he described became known as the “Butterfly Effect.”

The general idea is metaphorical, wherein the flap of a butterfly’s wings in one part of the world can, through a complicated series of cascading effects, create (or prevent) a big storm somewhere else. The essence of the concept is that small changes made within complex systems can have unintended consequences. The effects can appear quickly or slowly, close to the source of the disturbance or far away. And they are virtually impossible to predict, no matter how much time or money you have.

The butterfly effect has been described in weather forecasting, climate change predictions, human interactions, and even quantum physics.

I think it’s also a factor in the changes we have seen along the southwest Washington Coast over the past century. It emerged when we built big things in a complicated environment without fully understanding the consequences of our actions.

This is not a new idea: the results of a 2010 study conducted by Oregon State University sound a lot like the description of a butterfly effect related to the construction of the Columbia River jetties:

“It’s not unusual for construction of a jetty to cause some changes in the beaches and shoreline near it… But the impacts of the Columbia River jetties have just been amazing, the spatial scales of their influence are monstrous. I doubt when they were built anyone had a clue how significant their effect would be.” Peter Ruggiero, Oregon State University.

Let’s look at how things turned out at both ends of the road, starting with Westport and ending at Willapa Bay.

The Built Environment: Westport and the Big Rocks

“The Corps of Engineers is responsible for over 600 breakwaters and jetties, many of which date to the mid and late 1800s… Originally, the design and the construction of breakwaters and coastal protection structures were based on trial and error resulting from man’s conflict with nature. Later, existing experience was the guiding hand and it was not until the 1930s that model tests were introduced to aid in the design of such structures.” Design of Breakwaters and Jetties

My friend John Shaw, the Executive Director of the Westport South Beach Historical Society, calls the area around Grays Harbor “the built environment.” He’s right, and it’s epitomized by the jetties and other large infrastructure present in the region. When the jetties are maintained, the status quo mostly seems to prevail; when they fall into disrepair or are damaged, all bets are off, as we saw during the 1993 breach of the South Jetty.

Going forward, the Army Corps will spend enormous amounts of money to keep the navigational channel open, repair the jetty, and try various engineering fixes to make things safer and maybe more predictable. Despite these efforts, we may never fully understand how the jetties interact with the environment. Coastal engineers at Oregon State University studying the long-term impacts of the Columbia River jetties believe that even after 100 years, that system has still not reached equilibrium.

Wash Away No More?

“…the mouth of Willapa Bay is one of the more dynamic, high-energy systems along the coast – shaped by complex regional coastal processes such as waves, tidal flow, circulation, sediment transport, coastal geology and geomorphology. The area is a unique confluence of these interacting physical conditions that remain only somewhat understood.” 2017 Assessment of Coastal Erosion and Future Projections for North Cove, Pacific County

As you drive Highway 105 past North Cove and towards Tokeland, signs of engineering activity are everywhere, and so are the butterflies. Since the loss of the Willapa Light, federal and state agencies, coastal engineers, and local citizen groups have tried an assortment of both old and new technologies to keep the place from washing away. Construction crews work continuously to protect what is left of the road, mostly with large rocks, which are still the most dependable form of protection. Near Tokeland, the Army Corps recently completed a $40 million storm barrier to protect tribal land from continued erosion. While it’s too early to tell whether it will be an effective solution, the stakes are high: if the project fails, Shoalwater tribal lands that have been occupied for thousands of years could be lost, as could a multimillion-dollar oyster fishery representing 15% of the entire oyster industry in the United States.

One of the new technologies employed along Washaway Beach is called dynamic revetment. The idea is to place mounds of cobble and large woody debris parallel to the shore to create a substrate that reduces erosion in a more natural and cost-effective way. The revetments are like speed bumps that absorb the power of the ocean waves. This technique has shown promise in some locations, but it’s still too early to know if they will be an effective solution to the erosion.

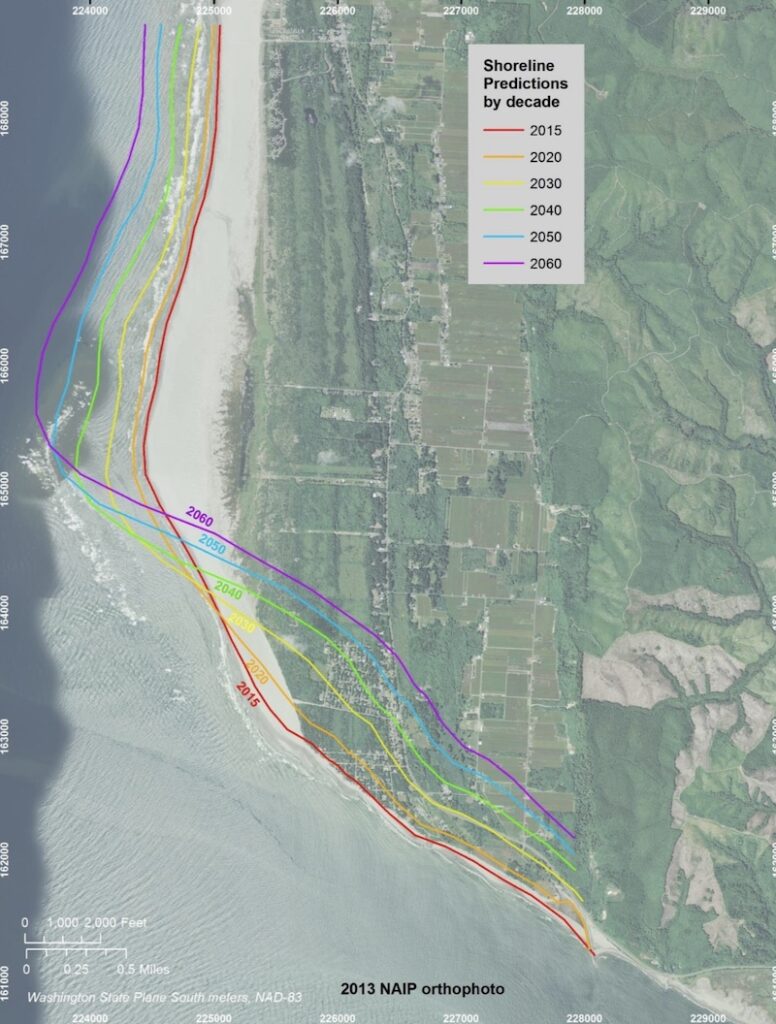

Although the Willapa Bay channel has stabilized in recent years and the erosion rate has decreased, coastal engineers admit they don’t know why it happened or how long it will last (a classic butterfly statement). Long-term erosion predictions remain grim. As shown below, over the next few decades, the north bank of Willapa channel is expected to continue to erode, erasing more homes, cranberry farms, and infrastructure, while beaches further to the north may actually grow. The high degree of uncertainty concerning the fate of the area leaves the Corps with “few feasible options for protecting the region.”

Final Thoughts

Learning the history of this small part of southwest Washington between Westport and Tokeland has given me a lot to consider. I think about how choices made a century ago have become legacies of the present (and the future, too) — and how everything we do affects something or someone else, sooner or later.

And going forward, I hope we can incorporate the most important lesson from the past into our future decisions: when we ignore the butterflies, we do so at our peril.

We now know that one way to avoid or minimize butterfly effects is to keep nature as close to its original state as possible, but I’m not sure how feasible that is in this built coastal environment that has already been changed so much.

For the residents of Grays Harbor, it must feel like they’re fighting a never-ending battle with the sea. During extreme high tides, for instance, it’s not uncommon for the ocean to send a big wave over the protective seawall and right down the main street of Westport, just to remind everyone who’s in charge.

The locals fight back with big rocks and enormous amounts of sand in some places, and build speed bumps out of little rocks and woody debris in others. The goal is always the same: to save their beaches and roads and communities from destruction so they can stay in this place a little while longer.

All the while, they think about connections and consequences, and try to keep the butterfly effects to a minimum whenever possible.

They keep on trying because this is their home, and there is no better place to be.

Information Sources

Grays Harbor General Information

Historical Bathymetric Changes Near the Entrance to Grays Harbor, Washington, T. L. Burch And C. R. Sherwood, Battelle/Marine Sciences Laboratory. Sequim, Washington, December 1992

Infrastructures of a Dynamic Landscape, South Beach, Washington, American Roundtable, Corey Mattheis and Robert Hutchinson,

Lighting the Way for Economic Development in Westport, Westport Golf Links, Economic and Fiscal Benefits Study, Sieger Consulting SPC, October 11, 2022.

National Register of Historic Places, Washington- Grays Harbor County.

Preparing Washington State Parks for Climate Change, A Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment for Washington State Parks, In partnership with the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, June 2017.

Ruth McCausland Passes at 101, Kat Bryant, The Daily World, September 14, 2020.

South Beach, Washington Infrastructures of a Dynamic Landscape, American Roundtable, Cory Mattheis & Robert Hutchison.

Washington’s Westport, Ruth McCausland.

Westport Light State Park – Westport Golf LLC Proposal Comments.

Westport South Beach Historical Society.

Aqua and Terra Incognita

Captain Robert Gray Enters Grays Harbor on May 7, 1792, Kit Oldham, January 13, 2003, HistoryLink.org Essay 5050.

Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest – Reading the Region: Discovering the Region.

Exploration in the Pacific Northwest Before the American Presence, Junius Rochester, April 23, 2003, HistoryLink.org Essay 5449.

Grays Harbor County — Thumbnail History, David Wilma, HistoryLink.org, May 27, 2006.

History of the South Beach, A Brief History of Westport, Ruth McCausland.

Swan, James G. (1818-1900), Kit Oldham Posted January 9, 2003, HistoryLink.org Essay 5029.

Washington State History for Kids.

Grays Harbor (Westport) Light

Grays Harbor Lighthouse, Graysharborbeaches.com.

Grays Harbor (Westport) Lighthouse, Lighthousefriends.com.

Grays Harbor Lighthouse, US Lighthouses.

Grays Harbor Lighthouse, Westport South Beach Historical Society.

Grays Harbor Jetties

Breach History and Susceptibility Study, South Jetty and Navigation Project, Grays Harbor, Washington, US Army Corps of Engineers, September 2006, Ty V. Wamsley, Mary A. Cialone, Kenneth J. Connell, and Nicholas C. Kraus.

Coastal Erosion Hazard Map: Westport, WA, people.uwec.edu.

Design of Breakwaters and Jetties, US Army Corps of Engineers, CECW-EH-D, Engineer Manual 1110-2-2904, EM 1110-2-2904, 8 August 1986.

Grays Harbor Estuary, Washington. Report 4, South Jetty Study: Hydraulic Model Investigation, Noble J. Brogdon, Technical Report (U.S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station) ; H-72-2 rept.4., US Army Corps of Engineers, September 1972.

Grays Harbor Navigation, US Army Corps of Engineers.

Groins and Jetties, National Park Service.

Historical Bathymetric Changes Near the Entrance to Grays Harbor, Washington, T. L. Burch and C. R. Sherwood, Battelle/Marine Sciences Laboratory, Sequim, Washington, December 1992.

History of North Jetty Construction, Ocean Shores, Washington, Washington Rural Heritage, Ocean Shores Heritage, January 9, 1991.

Impacts of the Grays Harbor Jetties, people.uwec.edu

Jetties Build Up Land, North Jetty, Ocean Shores, Washington, 1971-72, Washington Rural Heritage, Ocean Shores Heritage.

South Jetty Sediment Processes Study, Grays Harbor Washington: Evaluation of Engineering Structures and Maintenance Measures, Philip D. Osborne, Ty V. Wamsley, and Hiram T. Arden, US Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center, April 2003.

Westport Jetty Before & After, Urban Outcast, March 29, 2018.

Westport Jetty – Before and After, Urban Outcast: Chronicles of an Urban Redneck, March 29, 2018.

$10.9 Million Announced to Repair Ocean Shores Jetty; $40 Million to Restore Shoalwater Bay Berm, KRXO.com.

The Lost Lighthouse and Washaway Beach/North Cove

Analysis of Options for Maintaining SR 105 Near Washaway Beach, Jim Park, Senior Hydrologist, Garrett Jackson, Hydrologist, Rob Schanz, Hydrologist, WSDOT Environmental Services, Hydrology Program, July 2015.

Assessment of Coastal Erosion and Future Predictions for North Cove, Pacific County, Bobbak Talebi, George M. Kaminsky, Peter Ruggiero, Michael Levkowitz, Jessica McGrath, Katy Serafin, Diana McCandless, Publication No. 17-06-010, June 2017.

Assessment of Coastal Erosion and Future Projections for North Cove, Pacific County, Bobbak Talebi, George M. Kaminsky, Peter Ruggiero, Michael Levkowitz, Jessica McGrath, Katy Serafin, Diana McCandless, Washington State Department of Ecology, Publication no. 17-06-010, June 2017.

Coastal Erosion at Washaway Beach Erosion Analysis and Shoreline Change Predictions, George Kaminsky, Washington Department of Ecology.

Framework Geology of Cape Shoalwater and Northwest Willapa Bay, Washington, Assessing Potential Geologic Impacts on Recent Shoreline Change, Heidi M. Wadman, Jesse E. McNinch, and Jarrell Smith, US Army Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC), September 2020.

Graveyard Spit Restoration & Resilience Project, Washington Coastal Hazard Resilience Network.

How King County’s First State Representative Disappeared in Mysterious Shipwreck,

Feliks Banel, October 9, 2019, Mynorthwest.com.

North Cove: A Coastal Community vs the Pacific Ocean, A Project by the Washington Department of Ecology’s Coastal Monitoring and Analysis Program, Story Map by Tyler Cowdrey, June 4, 2020.

Pacific Coast Beaches Erosion and Accretion Report, James B. Phipps and John M. Smith,

Grays Harbor College, Aberdeen, Washington, July 1978.

Reading the Washington Landscape, Observations of Washington State Landscapes, Geology, Geography, Ecology, History, and Land Use, Cape Shoalwater or Washaway Beach, Dan McShane, September 20, 2010.

State of the Beach/State Reports/WA/Beach Erosion, Beachapedia.org.

The Experiment That May Have Saved a Washington Town From Falling into the Ocean, Erick Bengel, The Guardian, October 8, 2022.

The Willapa Bay Lighthouse, United States Lighthouse Society.

Washaway Beach, A Story of Place, Erick Langley, Washington Coast Magazine, February 19, 2016.

Washaway Beach, Cape Shoalwater, Eddie Jarvis, CoastalCare.org.

Washaway Beach, Fastest-eroding Place on the West Coast Cobbles Together a Solution, NBC News, Kathy Park and Tonya Bauer.

Washaway Beach: How a Community Stood Together and Refused to be Swept Out to Sea, Marguerite Garth, The Seattle Times, Pacific Northwest Magazine.

Washaway No More: The Eerie Story of North Cove, McNall Mason, Soozrustynail.com, January 1, 2021.

Willapa Bay Lighthouse, Lighthousefriends.com.

Willapa Bay Lighthouse, United States Lighthouse Society.

Willapa Bay Lighthouse – Lost Lights, Lietta, October 20, 2007.Baycenter.wordpress.com.

Willapa Light Station Opens on October 1, 1858, William S. Hanable, Essay 7067, HistoryLink.org, October 18, 2004.

Willapa Bay (Washington) Historical Light List Characteristics, US Lighthouse Society.

Willapa Bay and Tokeland

Corps of Engineers, Shoalwater Bay Indian Tribe Finish $40M Project, Michael S. Lockett, the Daily World, January 13, 2023.

Graveyard Spit Restoration & Resilience Project Preliminary Site Area Management Plan,Shorelands and Environmental Assistance Program, Washington State Department of Ecology, Olympia, Washington, Washington State Department of Transportation, Southwest Region Vancouver, Washington, 2022.

Graveyard Spit Restoration & Resilience Project, Washington Coastal Hazards Resilience Network.

Shoalwater Bay Berm Monitoring: 2014-2016 Assessment of Coastal Morphology Change,August 2017, Report number: 17-06-024Affiliation: Washington State Department of Ecology.

Shoalwater Bay Shoreline Erosion, Washington Flood and Coastal Storm Damage Reduction, Final Post-Authorization Decision Document and Final Environmental Assessment, Shoalwater Bay Indian Reservation, US Army Corps of Engineers, July 2009.

Big Rocks, Little Rocks, and Butterflies

Columbia River Jetties Changed the Face of the Pacific Northwest, Peter Ruggiero, Oregon State University, March 24, 2010.

Dynamic Coastal Protection: Resilience of Dynamic Revetments Under SLR (DynaRev), University of Bath, Water Innovation & Research Centre.

Dynamic Cobble Berm Revetments for Coastal Protection of High-Energy Coastlines, Chris Blenkinsopp, Paul Bayle, and Ollie Foss, University of Bath, Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering, January 26, 2023.

Dynamic Revetment Revealed as Top Choice for North Cove Shoreline Preservation, Dan Hammock, The Daily World, April 20, 2019.

The Butterfly Effect: The Impact of Deterministic Chaos on Our Lives, Anne-Laure Le Cunff, Ness Labs.

Understanding the Butterfly Effect, Jamie L. Vernon, American Scientist, Volume 105, Number 3, May-June 2017.

What Is the Butterfly Effect and How Do We Misunderstand It?, Nathan Chandler, Howstuffworks, Aug 7, 2020.

When the Butterfly Effect Took Flight, Peter Dizikes, MIT Technology Review, February 22, 2011.

0 Comments