You’ve all heard the term, but what does it mean when we’re talking about actual garbage?

When I was a kid, one of my favorite things was going to the dump with my dad. The city dump was run by a guy named Clarence Locke. Clarence kept an eye on things from the seat of a ramshackle Cushman three-wheeled scooter equipped with an enormous steel box on the front that he filled up with important stuff he found lying around. In addition to his salary, the city let Clarence sell anything of value he found in the trash and keep the money.

Clarence used the scrap lumber people threw away to build a series of buildings equipped with shelves to display his wares. His “retail store” looked like a weird marriage between a strip mall and a swap meet–a place where you could buy amazing things really cheap. My dad would give me 50 cents, or maybe a dollar on my birthday, and turn me loose in those buildings. I would come home with an old typewriter, a used bicycle, or maybe a pair of ice skates, even though they were three sizes too big and there wasn’t an ice-skating within 50 miles. I still have two antique phones built in the early 1900s out of dovetailed oak hanging on the walls of my home. My dad bought them from Clarence.

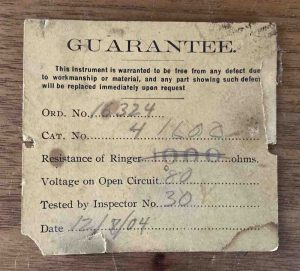

This is the guarantee I found inside one of the old hand-crank phones my dad purchased from Clarence.

Phones like these were built to last.

They were both functional and works of art.

If they quit working, they could be fixed.

AND they served us well for over 40 years–the final hand crank phone was replaced by “modern” technology in 1952.

Time passed, and when Clarence died, there were rumors that he was a millionaire, living the dream in a workplace we now know was likely a hazardous waste site. He made his living carrying on a tradition of reusing things that he likely learned from growing up during the great depression, when everybody did it because everybody was poor.

Where Does it Stop?

The past couple of years, I’ve been thinking a lot about garbage, prompted by recent recycling restrictions imposed by China and a “recycling” audit conducted in my community that determined that most of us aren’t doing it right. This got me thinking about Clarence and garbage dumps. And I concluded that there has to be a better way to deal with our growing mountain of municipal solid waste (MSP). Kudos to the facilities that recycle used oil, antifreeze, steel, and refrigerators, and to the nonprofits that take in our throwaways and resell them for a small profit. Despite their efforts, an enormous amount of stuff still makes its way to dumping grounds we now call “sanitary landfills.” I decided it was time to examine both the issues and challenges of garbage, and to take a closer look at my own behaviors and how I might reduce my environmental footprint. Here’s what I found out.

Interesting Things About Dumps and Dumping

The first interesting thing about dumps and dumping is sort of self-evident: humans have been throwing things away for a very long time. Organized waste and wastewater management probably began around 2,000 years ago by the Romans, of course. In addition to building sophisticated aqueducts to provide clean water, they also devised cool ways to deal with human waste and garbage in large population centers. Some archaeologists believe that the Roman answer to their garbage problem was to collect it from the streets using donkey carts, transport it to an area outside of town, dump it on the ground, then periodically add layers of dirt to keep down the smell and vermin. Sound familiar?

In 2013, Isralie archaeologists stumbled upon the “mother of all garbage dumps” in the Kidron valley near Jerusalem. The dump rose over 70 meters from the valley floor to the walls of an ancient city. Garbage-dump archaeology has also helped us to understand how ancient cultures lived and sometimes even why they disappeared. Incredibly, one of the oldest biblical writings (fragments of the Gospel of Mark), dating to the second or third century, was discovered in an Egyptian garbage dump.

We’ve also gotten really good at creating colossally large piles of garbage brimming with environmental hazards.

One of the world’s largest dumps, the Bantar Gebang Landfill located in Jakarta, Indonesia, covers an area equal to 200 football fields and rises to a height of over 200 feet. About 7,000 tons of trash arrive every day, and between 6,000 to 20,000 people live near the dump, scavenging and reselling the valuable things they find. This is a massive public health problem, and people have died there from impalement when they slip and fall from the mountains of garbage or by being buried in “garbage avalanches.” The site is now serving as a test bed for innovative technologies to reduce the volume of waste or convert it to energy, but the task ahead is enormous. A quote from an article published by Vice gives you an idea of what the garbage scavengers have to deal with on a daily basis:

“We slip a lot, especially when it rains. It’s summer now, but it’s not like this during the rainy season,” Edi said. “We stop [when it rains]. We are careful to watch where we step. When the wind is strong, we all come down from the mountain.”

The ‘World’s Largest Dump’ Is in Indonesia and It’s a Ticking Time Bomb

Vice Indonesia

https://www.vice.com/en/article/7x54jd/the-worlds-largest-dump-is-in-indonesia-and-its-a-ticking-time-bomb

The second interesting thing about dumps and dumping is also kind of self-evident: because we’ve been throwing things away for so long, the management of solid waste has grown into an international business behemoth that involves public health professionals, scientists, engineers, politicians, doctors, lawyers, and ordinary folks. Everywhere you go, there are people and infrastructure dedicated to dealing with what we throw away. These people wake up in the morning and go to bed at night thinking about garbage, and we should thank them.

Researching this article also reminded me that local, state, and federal agencies spend a lot of time thinking about landfills, and some of them write extremely detailed and intense reports full of charts and graphs that are published in trade and scientific journals dedicated to various aspects of waste management. Colleges, universities, and trade schools are also heavily involved, offering certifications, advanced engineering degrees, and PhDs in waste management disciplines. With offshoots in public health, environmental sustainability, energy, and more, the employment opportunities are endless!

The third interesting thing about dumps and dumping is less self-evident, but equally important: location matters. I know a little about this topic through my past environmental work, and some local examples remind me that we need to be careful where we dump and bury things. Here are two examples of why location (and decisions) matter.

The Beach Glass Beach, Port Townsend, WA

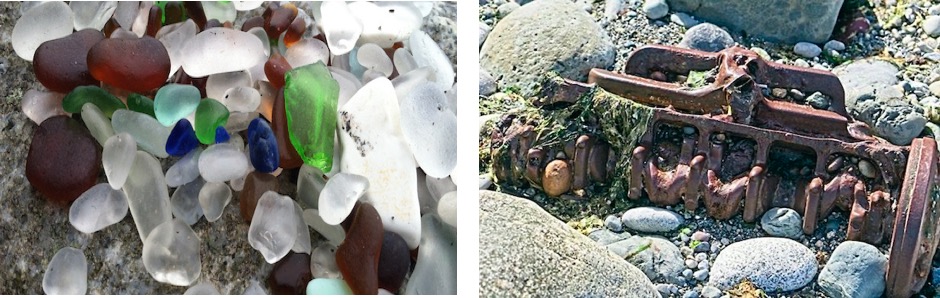

There’s a beach not far from where I live that is really popular with the locals because it’s a great place to find beach glass.

On a good low tide, you can walk for a couple of miles and find places where the broken glass, polished by the waves, collects. You will also find other things that are not what you might expect to find on a beach. The interesting piece of metal in the right-hand photo may be the remains of a truck motor, I think, polished smooth by the waves and sand.

Glass, pieces of pottery, and old car parts have collected at the beach because it is adjacent to an old dump site. Back in the day, folks used to back their trucks right up to the edge of the bluff and toss things over the cliff to the water below. The lighter things were taken away by the tide, but many of the heavier things remain to this day. Are the things buried there a hazard? I’m not sure anyone knows.

The Landfill That Didn’t Stay Filled, Port Angeles, WA

This example is a cautionary tale of what happens when a landfill is situated on a high bluff adjacent to a significant waterway, and then around a hundred years later, when the bluff fails and stuff starts leaching out, falling on the beach, and entering the water, people realize that they have an expensive problem on their hands. The picture above shows the general layout of what is now a transfer facility in Port Angeles, WA; in the top part of the photo, you can see the beach and the Strait of Juan de Fuca, directly adjacent to old landfill cells that have now been stabilized. And yes, that is a cemetery over to the right.

As with the Beach Glass site, early dumping practices along the Strait often involved pulling up to a handy bluff and pushing things over the edge. The current Port Angeles site was acquired in the 1940s, and all manner of things were dumped very close to the edge over the next 60 years, including municipal and industrial waste, car bodies, and most likely chemicals and waste we would consider toxic today. Over time, erosion of the 135-foot bluff separating the dump from the Strait partially collapsed, causing compacted garbage and waste to contaminate the shore and enter the water. To date, the cost of fixing this mess has exceeded $20 million.

Thus, one old landfill placed close to shore eventually created a beach glass collecting paradise while another created a massive financial headache for a small city. Neither should have been located where they were and would never be allowed today.

What We Throw Away

In many ways, dumps are time capsules that help us understand ancient, and even more recent cultures. Shell middens found in coastal areas of the Northwest give us a glimpse of what life might have been like for Native American and First Nation peoples, as do bits of pottery and tools dug up in the yard of a historic homes in New England. Dump-diggers are still active now, rummaging around in old ghost towns and settlements to find bits of the past.

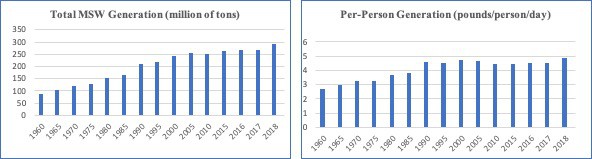

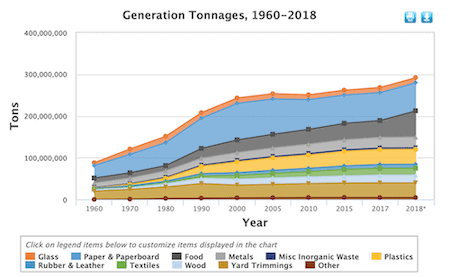

Thankfully, the EPA has made life easier for me by summarizing a lot of information concerning municipal solid waste practices into some handy graphs that I will now use to torture you.

The left graph shows how much municipal solid waste (MSW) we have been generating over the past six decades. In 1960, we generated about 88 million tons; in 2018, it was almost 300 million tons- equivalent to the weight of 1.5 million Boeing 747 airplanes (if I did the math right). Although an increasing population is partly responsible for the increase in total waste tonnage, the graph on the right shows that per-person waste generation has almost doubled since 1960. We now generate nearly 5 pounds of waste per person per day, compared to about 2.7 in 1960. The good news is somewhere in the mid-1990s, per-person waste generation began to flatten out. But we still generate a lot of waste compared to the folks living in the 1960s.

Shame on us.

But on the Flip Side….

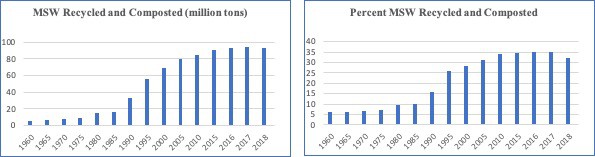

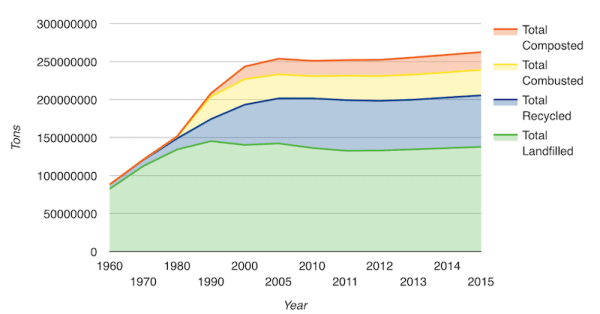

Here are a couple of graphs that show how well we’ve been doing with regards to recycling and composting.

The graph on the left shows some encouraging signs: back in 1960, we recycled and composted about 5.6 million tons of waste. We’re now recycling and composting about 94 million tons. If you look at recycling numbers as the percent of our total waste generation (right graph), you can see that we’ve improved over time, but have struggled to get above the 35% recycling mark. The EPA states that the volume of waste in landfills has decreased from 94% of the amount generated in 1960 to 50% of the amount generated in 2018. That sounds good, but to me, putting half of your waste in the ground after all these years doesn’t seem good enough, given how smart we think we are. We’ll talk about this a bit later.

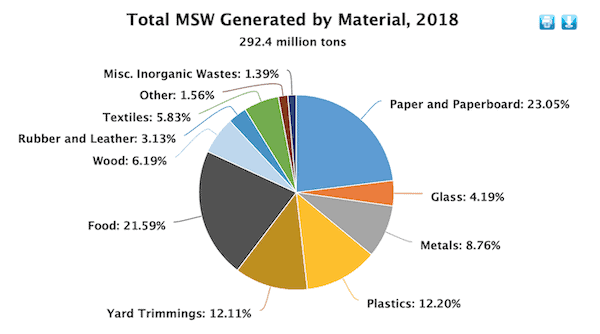

MILLIONS of TONS? What’s IN all that Stuff?

I bet you’re wondering what makes up the 300 million tons of stuff we brought to the landfills in 2018.

The EPA folks have the answer to that, too.

As you can see, the big four are paper/paperboard, food, plastic, and yard trimmings. We also bring a lot of glass and metals to our local landfill or transfer station. Although it bothers me that over 20% of our waste generation is food that’s being thrown away, at least it’s compostable, as is yard waste. And we know technologies for recycling paper, glass, and metals have been around for decades, so that is good.

Composition Over Time: How Our Garbage Reflects Changes in our Society

This graph is really interesting. The first thing you notice is that paper, food, and yard trimmings have been a constant part of our waste stream since the 1960s. The one that caught my eye is the yellow band: plastic. In 1960, we brought about 390,000 tons of plastic to landfills, representing less than 0.5% of our waste stream. In 2018, the number was 26,970,000 tons- about 9% of the total. And given how light plastic is, and how long it lasts in the environment, this looks like something we should care about.

Based on the graphs, I’m thinking there are two things we should consider going forward:

- Explore what can we do to reduce the total volume of stuff we bring to landfills in the first place, and

- Consider our options for recycling BEFORE we purchase, especially given all the uncertainties we have concerning who will take what and whether things sent to a “recycling center” are actually being recycled.

The Fate of Our Garbage

Ever wonder where your trash goes when you say goodbye to it at the curb or transfer station? Probably not, if you’re like most Americans. And I admit that even I didn’t know the answer to this question until I did some local, regional, and national internet sleuthing.

According to the Rockefeller Institute, about half of the solid waste generated in the U.S. still goes into a landfill. We recycle a little over 25%, burn about 13%, and compost the rest (about 9%). Speaking of recycling, we used to send a lot of our recyclables to places like China and southeast Asian countries, including Indonesia, the home of Bantar Gebang. However, in 2018, China enacted more stringent standards for recyclable imports, and other nations have followed suit. Many of our “recyclables” were not making the cut, so many of these countries started returning our barges of trash, increasing our already large waste management problem and serving of a visual reminder that we’re not really dealing with our stuff.

The Future of Trash

As noted above, we currently have four ways to deal with our trash: put it in a landfill; combust it to create heat or electricity (or to just reduce its volume), compost it, or recycle/reuse it. In the bad old days, there was a fifth option, ocean dumping, but thankfully that was outlawed in the U.S. in 1988, although it still occurs elsewhere in the world, with China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam being the worst offenders, at a terrible human and ecological cost. As with all things, our current choices have both upsides and downsides. We already know what can happen at landfills, especially the old, abandoned ones situated in the wrong kinds of places, or the hell-hole dumps in other countries. But what about recycling/reuse, combustion, and composting? Some good things are happening for all three that will make them more effective options going forward.

Recycling and Reuse should be a no-brainer, but as a country, we’re not that good at it yet. Other developed countries (and especially island nations) are leading the way in recycling, and we should pay close attention to how they are doing it. For many years, one of our primary recycling strategies was to send the collected stuff to China, Thailand and its neighbors, or India. We are now focusing on in-country recycling, but there are challenges. First, in order to be profitable, recycling has to be local, because shipping costs heavily influence profits. As noted by NREL, if glass is transported more than 100 miles, it’s cheaper to just make new glass. Tin and aluminum recycling are mature technologies, but more could be done to improve the processing while decreasing costs. Plastic is difficult because there are so many kinds, and some are a pain to handle and process.

By restricting the importation of recycled plastic, China may have done us a favor. We now have smart people exploring how to improve recycling processes, including the use of robots and artificial intelligence to automate sorting processes, making it easier, safer, and more cost-effective to handle complicated recycling waste streams. And there are new startup companies creating innovative ways to use recycled plastic to make things like clothes, housewares, sporting goods, and construction materials. All of these things will make recycling more attractive to investors, and could be a turning point in our struggle to reduce the volume of material that goes into landfills. In the meantime, we really should minimize the things we buy that are not recyclable.

Re-use is something all of us already do but should consider more in our purchases. Using an empty mayonnaise jar to hold your miscellaneous screw collections might bypass the landfill for now, but eventually your children will have to deal with your stuff after you’ve moved to the great beyond. My kids are acutely aware of this.

After we figured out how to create and use fire, Combustion became a handy way for ancient cultures to burn waste. The old-style garbage dumps often caught on fire, providing a handy but toxic way to reduce waste volume. Waste combustion/incineration earned a bad reputation in the middle 20th century because of excessive air pollution and sloppy waste handling practices. It’s still not popular with those living near biocombustion facilities, despite improvements in emissions and better waste handling. It’s also generally cheaper to send waste to a landfill than it is to incinerate it.

The big problem with waste combustion (and the thing that makes it expensive) is dealing with waste products created or left behind. “Fly ash” is the light stuff that swirls around and escapes up the chimney during combustion that must be trapped or filtered to reduce air pollution; “bottom ash” is the stuff left at the bottom of the incinerator at the end of a burning cycle that requires disposal (often in a landfill). Both can be toxic and may require special handling and disposal.

New technologies are emerging to provide more efficient, complete burning of waste with less toxic emissions. Engineers are also looking at ways to mine the burn residues for metals and useful chemicals, and techniques for making the ash products suitable for construction materials. Is there hope for combustion technologies? Maybe, if the technical and cost challenges can be overcome.

Composting is probably the most familiar way to deal with biodegradables. Many landfills now offer composting of yard waste and other materials as a service and then sell the final product back to us at a reasonable cost. The latest trend in the composting world is in the fabrication of compostable products – everything from containers to packaging – and some of these innovative companies creating single-use compostable products are getting the attention of major corporations. Many of these innovators believe recycling is a failed concept and that the future is in creating products that are used and immediately composted. Keep an eye on this.

Final Thoughts

Figuring out how to end this article has been a bit of a challenge. If you look closely at the numbers related to waste generation and management, it’s kind of hard to determine how well we’re actually doing. The first part of this article seems to paint a semi-grim picture of our consumer-focused society and the emergence of new types of waste streams, like plastic, that are finding their way into our food and water supplies. The second part suggests a lot of good things happening on the recycling front, and the intellectual horsepower out there looking for solutions is encouraging. Maybe a new breed of scientists and engineers will help us clean up the past – or not. We can no longer afford to ignore the problem or stop trying to make progress.

At any rate, I’ve reached a couple of personal conclusions regarding my behaviors and their effect on the planet that involve buying less stuff I don’t need, and dramatically reducing the amount of plastic waste I generate, recyclable or not. For instance, I’ve switched to glass milk bottles because they can be easily cleaned and reused. Besides, I like glass milk bottles.

Waste reduction is kind of a no-brainer action that can be reached without the benefit of a fancy engineering degree or a career in solid-waste management. But it turns out somebody with those type of skills and experience made the best common-sense case to me for why waste reduction is important. Here is what he said:

“Source reduction absolutely makes sense. Why? Three-quarters of the cost to manage MSW is in collecting it. There is absolutely no reason to produce waste to recycle it or use it as a fuel if you don’t have to make it at all.”

Donald K. Walter, former Municipal Solid Waste Program Manager for the U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/legosti/old/26040.pdf

As I wrap up this article, I find myself thinking again about Clarence, the caretaker of the city dump. I wonder what he would make of this world where mountains of garbage are piling up and up and up, composed mainly of things that are made to be thrown away. In his time, products were made to last, could be repaired, and often moved from one owner to another.

Despite all the technological progress we have made, we are still collecting waste door-to-door, transporting the majority of it to an out-of-the-way place, and covering it with dirt.

Just like the Romans did.

And in the distant future, maybe an inquisitive archaeologist will excavate one of our vast landfills filled with nasty, toxic crap and broken things and wonder:

“What were these people thinking?”

Information Sources

Introduction

Spanning Time: When Phones Meant Hand Cranks, Operators and Party Lines. Gerald Smith, Special to Binghamton Press & Sun-Bulletin, January 18, 2019. https://www.pressconnects.com/story/news/connections/history/2019/01/19/spanning-time-when-phones-meant-hand-cranks-operators-and-party-lines/2608702002/

Ancient Garbage Dumps

1,500-year-old Garbage Dumps Reveal City’s Surprising Collapse. National Geographic, March 25, 2019. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/ancient-garbage-dump-elusa-reveals-surprising-city-collapse

Ancient Romans, Jews Invented Trash Collection, Archaeology of Jerusalem Hints. HAARETZ, June 29, 2016. https://www.haaretz.com/archaeology/.premium-ancient-romans-jews-invented-trash-collection-1.5402478

One of the World’s Oldest Bible Passages Found in Egyptian Garbage Dump. Nile FM. https://nilefm.com/news/article/1507/one-of-the-world-s-oldest-bible-passages-found-in-egyptian-garbage-dump

Gospel of Mark Fragment Found in Egyptian Garbage Dump Is Not From 1st Century. Christian Post, May 29, 2018. https://www.christianpost.com/news/gospel-of-mark-fragment-found-egyptian-garbage-dump-not-first-century.html

Bantar Gebang Landfill, Jakarta, Indonesia

The ‘World’s Largest Dump’ Is in Indonesia and It’s a Ticking Time Bomb. Vice Indonesia. https://www.vice.com/en/article/7x54jd/the-worlds-largest-dump-is-in-indonesia-and-its-a-ticking-time-bomb

Jakarta’s Trash Mountain: “When People are Desperate for Jobs, They Come Here.” New York Times, April 27, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/27/world/asia/indonesia-jakarta-trash-mountain.html

Living off the Landfill: Indonesia’s Resident Scavengers. The Guardian, September 27, 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/sep/27/indonesia-waste-tip-scavengers

Beach Glass Beaches

Port Townsend: “Glass Beach” Sparkles Even if Remnants of Former City Dump are Gone with the Tides. Peninsula Daily News, November 5, 2004. https://www.peninsuladailynews.com/news/port-townsend-glass-beach-sparkles-even-if-remnants-of-former-city-dump-are-gone-with-the-tides/

Olympic Peninsula – North Beach, Port Townsend, WA. Pacific NW Beachcombing, February 9, 2016. https://www.pnwbeachcombing.com/field-reports/olympic-peninsula-north-beach-port-townsend-wa

The Landfill That Didn’t Stay Filled

Trash Pushed Over the Bluff: Port Angeles Regional Dump Abuse Goes Back Decades. Peninsula Daily News, April 20, 2014. https://www.peninsuladailynews.com/news/trash-pushed-over-the-bluff-port-angeles-regional-dump-abuse-goes-back-decades/

Port Angeles Landfill Stabilization. Herrera. https://www.herrerainc.com/projects/port-angeles-landfill-stabilization/

Port Angeles Landfill. Watershed Geo.https://watershedgeo.com/project-profiles/port-angeles-landfill/

Clallam CountyComprehensive Solid WasteManagement Plan Update 2014. Clallam County Washington. http://www.clallam.net/boards/SWAC/documents/2014CCCSWMPFinalAndAppend.pdf

What We Throw Away

National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling. US Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/national-overview-facts-and-figures-materials

Managing America’s Garbage. National Renewable Energy Laboratory, March 1996. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/legosti/old/26040.pdf

The Fate of Our Garbage

Where Does Our Garbage Go? Rockefeller Institute, September 11, 2019. https://rockinst.org/blog/where-does-our-garbage-go/

Understanding Where Garbage Goes. Earth 911, October 25, 2019. https://earth911.com/business-policy/understanding-where-garbage-goes/

The Future of Trash

5 Countries Dump More Plastic Into the Oceans Than the Rest of the World Combined. Patrick Win, PRI Global Post, January 13, 2016. https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-01-13/5-countries-dump-more-plastic-oceans-rest-world-combined.

An Insightful Short Film Follows a 90-Year-Old Fisherman Who Clears Plastic from Bali’s Coasts. Colossol, July 6, 2021. https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2021/08/dana-frankoff-voice-above-water/

Rise of the Recycling Robots. Forbes, November 12, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrickcai/2020/11/12/rise-of-the-recycling-robots/?sh=5e991bff65f9

How Robots are Helping Us to Recycle Better. American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), January 13, 2020. https://www.asme.org/topics-resources/content/how-are-robots-helping-us-to-recycle-better

Trillions of Pounds of Trash:New Technology Tries to Solve an Old Garbage Problem. Catherine Clifford, NBC Disruptor/50, May 20, 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/29/can-new-technology-solve-a-trillion-pound-garbage-problem.html

‘Plastic Recycling is a Myth’: What Really Happens to Your Rubbish? Oliver Franklin-Wallace, The Guardian, August 17, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/aug/17/plastic-recycling-myth-what-really-happens-your-rubbish

Managing America’s Garbage. National Renewable Energy Laboratory, March 1996. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/legosti/old/26040.pdf

After Incineration: The Toxic Ash Problem. IPEN Dioxin, PCBs and Waste Working Group, April 2005. https://ipen.org/sites/default/files/documents/After_incineration_the_toxic_ash_problem_2015.pdf

Emerging Waste-to-Energy Technologies: Solid Waste Solution or Dead End? Nate Seltenrich, Environmental Health Perspectives, 2016 Jun; 124(6): A106–A111. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4892903/

Energy Recovery from the Combustion of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW). US Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/smm/energy-recovery-combustion-municipal-solid-waste-msw

0 Comments